Awareness with recall after general anesthesia is an infrequent, but well described, phenomenon that may result in posttraumatic stress disorder. There are no recent data on the incidence of this complication in the United States. We, therefore, undertook a prospective study to determine the incidence of awareness with recall during general anesthesia in the United States. This is a prospective, nonrandomized descriptive cohort study that was conducted at seven academic medical centers in the United States. Patients scheduled for surgery under general anesthesia were interviewed in the postoperative recovery room and at least a week after anesthesia and surgery by using a structured interview.

Data from 19,575 patients are presented. A total of 25 awareness cases were identified (0.13% incidence). These occurred at a rate of 1–2 cases per 1000 patients at each site. Awareness was associated with increased ASA physical status (odds ratio, 2.41; 95% confidence interval, 1.04 –5.60 for ASA status III–V compared with ASA status I–II). Age and sex did not influence the incidence of awareness. There were 46 additional cases (0.24%) of possible awareness and 1183 cases (6.04%) of possible intraoperative dreaming.

The incidence of awareness during general anesthesia with recall in the United States is comparable to that described in other countries. Assuming that approximately 20 million anesthetics are administered in the United States annually, we can expect approximately 26,000 cases to occur each year.(Anesth Analg 2004; 99:833–9)

Awareness with recall after surgery under general anesthesia is an infrequent but well described adverse outcome

The occurrence of awareness is often the consequence of light-anesthetic techniques or smaller anesthetic doses 6, 7. All data on the incidence of awareness during anesthesia come from outside the United States (US). Sandin et al. (3) reported an overall incidence of 0.16% in 11,785 patients treated at 2 hospitals in Sweden; the rate was 0.18% when neuromuscular blocking drugs were used and was 0.11% in their absence. Long-term follow-up of the patients who reported awareness showed a frequent incidence (approaching 50%) of PTSD 2 yr after the incident, even though patients initially did not report much distress 8. In a study from Australia, Myles et al. (2) reported an incidence of awareness of 0.10%; it was the highest risk factor for patient dissatisfaction after anesthesia.

Traditional clinical monitoring modalities during anesthesia are ineffective in preventing awareness. For instance, hypertension and tachycardia are generally not associated with reports of awareness 5, 7, and end-tidal anesthetic concentration monitoring is also ineffective 3. Recently, a monitor that uses a processed electroencephalogram (EEG) derivative, the Bispectral Index® (BIS®; Aspect Medical Systems, Newton, MA) has been introduced into clinical practice for monitoring anesthetic effects on the brain 9,10. It may have the ability to measure the hypnotic component of the anesthetic state 10.

The effectiveness of BIS monitoring to prevent awareness is unknown 11, and it has even been suggested that guiding anesthetic administration by using BIS monitoring may be associated with an increased incidence because of deliberate reductions in anesthetic dose on the basis of BIS data 12.

Although the incidence of awareness is thought to be infrequent, many patients remain concerned about this potential adverse experience 1, 2, and this issue has attracted considerable public media attention.

The incidence of awareness may vary between countries or institutions depending on their respective anesthetic practices and patient populations.

This multicenter prospective cohort study was therefore undertaken to establish the incidence of awareness with recall during routine general anesthetic practice in the US and to determine (where possible) the BIS values associated with intraoperative awareness events. Methods The IRBs at seven geographically dispersed academic medical centers approved this prospective, nonrandomized, descriptive cohort study. Patients with informed consent (written or verbal, depending on site) were enrolled between April 2001 and December 2002.

Inclusion criteria were patients scheduled to receive general anesthesia, aged 18 yr, apparently normal mental status (excluding obviously impaired patients), and ability to provide informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were not expected to survive, were transferred directly to the intensive care unit (ICU) and were not tracheally extubated within 1 wk, could not speak English, or had abnormal mental status that precluded answering the required questions. A sample size of 20,000 patients was estimated on the basis of previous incidence studies outside the US 3.

Anesthetic care, including anesthetic drugs and use (or otherwise) of the BIS monitor (A2000 or A1050; Aspect Medical Systems) during the time of this study was entirely at the discretion of the attending anaesthesiologist and was not influenced by participation in this study. In general, the attending anaesthesiologist was not aware of patient participation in the study. Each patient was interviewed by research staff with the same structured interview, modified from Brice et al. 13, that was used in prior incidence studies 3,13,14 (Table 1).

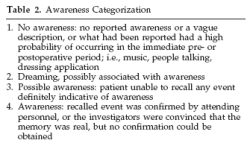

Patients were interviewed first in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) (if they were sent to the PACU and not directly to the ICU). At one site, the IRB required the interview to be conducted after the patient had left the PACU. A follow-up interview was attempted at least 1 wk after anesthesia. The principal investigators classified each patient report as awareness, possible awareness, dreaming, or no awareness, according to the definitions described in Table 2.

Basic patient demographic and treatment data (e.g., age, sex, ASA physical status, type of surgery, and disposition after anesthesia) were also recorded on a standardized case report form used by all participating sites. In cases in which awareness was detected and BIS monitoring had been used, available BIS trends were retrospectively downloaded from the A2000 monitors’ electronic memory. Each patient with awareness was offered follow-up care according to each institution’s standard practice.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the incidence of awareness in the study population.

Comparisons between groups were conducted with Fisher’s exact or 2 tests with Yates’ correction.

Logistic regression models (SPSS; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) were used to determine associations of patient demographics with awareness and dreaming. Variables found to be significant on univariate analysis were entered into the forward-selection multivariate model. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

A total of 20,402 patients were initially enrolled, but 827 patients (4%) were excluded because they could not be interviewed after surgery (n _ 793) or did not meet the inclusion criteria (n _ 34), resulting in a final evaluable population of 19,575 patients. Eighty-five percent (n _ 16,544) of the evaluable patients were interviewed in the recovery room, and 67% (n _ 13,123) completed the postoperative follow-up interview (Table 3).

The postoperative follow-up interview occurred between 1 and 2 wk in most patients (n _ 9535; 73%), with follow-up at more than 2 wk in 24% (n _ 3216) and less than 1 wk in 3% (n _ 372). In the recovery room, 49 patients (0.30% of interviewed patients) reported remembering something between going to sleep and waking (yes to Question 3 in Table 1), whereas 80 (0.61%) reported intraoperative memories on the postoperative follow-up interview.

Six percent (994 of 16,544) of patients reported dreaming (yes to Question 4 in Table 1) during the recovery room interview, and 3.43% (439 of 13,123) reported intraoperative dreams on the postoperative follow-up.

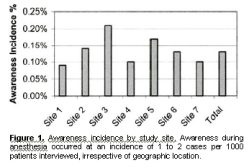

From these interviews, 25 awareness cases (0.13%) were identified (see Table 4 for detailed patient descriptions of recollections). Awareness during anesthesia occurred at a fairly consistent rate of 1–2 cases per 1000 patients interviewed at each institution (range by site, 0.09%–0.21%; Fig. 1).

In addition, 46 additional cases (0.23%) of possible awareness and 1183 reports of intraoperative dreaming (6.04%) were identified. Fourteen of the cases of awareness were identified only at the followup interview. Auditory perceptions and being unable to move or breathe were described by nearly half of the patients with awareness (Table 5). Anxiety/stress, pain, and the sensation of the endotracheal tube were also reported (Table 5). The demographic characteristics of patients with awareness and possible awareness compared with no awareness are listed in Table 6. Logistic regression analysis demonstrated an association of awareness with increased ASA physical status, final disposition to the ICU, and procedure (abdominal, thoracic, cardiac, and ophthalmology versus other). ICU disposition was eliminated from the multivariate model (Table 7). Sex and age did not influence the incidence of awareness. There were no significant predictors of possible awareness. The incidence of dreaming varied markedly by site (1.1%–10.7%; P _ 0.001).

Dreaming was associated with the following patient characteristics: younger age (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 2.03–2.91 for _40 yr compared with _60 yr), lower ASA physical status (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, m1.29–1.70 for ASA status I–II compared with ASAm status III–V), undergoing elective surgery (OR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.04–6.15 compared with emergency surgery), and undergoing surgery on an ambulatory basis (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02–1.91 compared with disposition to ICU). Thirty-eight percent of all cases in the study werem monitored for portions of each case by using BIS. However, the use of BIS monitoring varied widely between study sites from 0% to 74% (P _ 0.001), and not all cases that were BIS-monitored were monitored from induction to emergence. Figure 2 illustrates a case of awareness with BIS monitoring. BIS was consistentlym _60. There was no significant associationm between the use (or otherwise) of BIS and the incidence mof awareness.

|

Table 4. Descriptions of Awareness | ||||

|

Age (yr) |

ASA status |

Procedure type |

Anesthetic |

Description |

|

77 |

II |

Ophthalmic |

Propofol, fentanyl, nmb |

The patient reported waking up during the operation and felt the surgeons working on her eye and could hear them talking. She tried to move and talk but could not and felt helpless. There was no pain. |

|

21 |

I |

Ophthalmic |

N2O, propofol infusion, fentanyl, nmb |

The patient said that she heard the chief surgeon or a male voice saying “careful, careful” and “to the left.” The voices “faded in and out.” No other sensation or discomfort. The experience did not bother her at the time. |

|

49 |

II |

Abdominal |

Isoflurane, fentanyl, nmb |

The patient recalled “a great deal of conversation.” She recalled hearing conversations about her tattoos and what they found in her abdomen. She remembered being unable to move and “it was like being in a box. It was dark and I could not move at all.” |

|

29 |

I |

Lower abdominal |

N2O, isoflurane |

The patient reported an “out of body experience” at some point during the surgery with her floating out of her body and watching the surgery from above. She thought it was very “weird.” She thought frequently about it. |

|

28 |

I |

Orthopedic |

Propofol, remifentanil |

She remembered waking up and feeling the tube in her throat. She wanted to make sure that the anesthesiologist knew that, because she did not know whether the surgery was still going on or not. |

43 |

II |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

Isoflurane, N2O, fentanyl, nmb |

“Feeling tube going down throat and could not breathe” was last thing remembered. “I tried to open my eyes and couldn’t. I tried to move my fingers. I then tried to breathe and couldn’t.” |

|

31 |

III |

Orthopedic |

Sevoflurane, propofol, N2O, fentanyl, nmb |

Reported choking on tube. Worst thing was “felt like couldn’t breathe.” |

|

66 |

III |

Orthopedic |

Sevoflurane, propofol, N2O, fentanyl, nmb |

“During this surgery I became conscious. I was in total darkness; I was paralyzed. I felt as if I wanted to take a few breaths, but I couldn’t. It was a terrible experience. After a few minutes I lost consciousness.” |

|

40 |

III |

Abdominal |

Sevoflurane, fentanyl, nmb |

Reported “Yes, feeling pain, cutting, someone asking for scalpel, feeling of cutting.” Worst thing was “waking up in OR while paralyzed.” “I woke up during the procedure and could hear the doctors talking and I could feel the pain in my wound. I was not able to move or speak and it is one of the worst scares I’ve had in my long history of serious illness.” |

|

63 |

III |

Abdominal |

Sevoflurane, propofol, N2O, nmb |

Reports “not being able to breathe, trying to move my hand to let them know I felt the mask being forced on my face and no air, couldn’t breathe, finally said this is it, I’m going to die and thought to myself ‘Oh well, the hell with it’ and just gave up.” |

|

53 |

II |

Head and neck |

Propofol, fentanyl, nmb |

“I remember trying to talk to them and telling that I was awake.” “I woke up during surgery enough to know that I was in surgery and was trying to figure out a way to tell them I was awake. I knew my arms were tied and my eyes were taped shut. PANIC!!” |

|

49 |

III |

Abdominal |

Sevoflurane, propofol, fentanyl, nmb |

He tried to open his eyes but couldn’t; tried to move his arms, couldn’t. Heard conversations in OR. |

|

63 |

IV |

Redo coronary artery surgery |

Thiopental, isoflurane, fentanyl |

Experienced the sound of somebody asking about liquid on floor. Heard that the doctor forgot to connect the catheter of the bag; the floor was full of urine. Other jumbled conversations, someone was angry and yelling about it. All these ran together. |

|

49 |

III |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

Propofol, desflurane, N2O, fentanyl, nmb |

Recollections with lights, sounds, noises, lots of noises, pain, sound of somebody asking “Where are you going? What are you doing?” The patient was unable to talk; felt like she was in a hurricane and had a sensation of wanting to get out. |

|

67 |

IV |

Coronary artery surgery |

Thiopental, isoflurane, fentanyl, nmb |

People were talking to each other saying things were okay. He tried to talk to tell them that he couldn’t breathe. No one was paying attention. Arms felt to be fastened down, had severe chest pain. |

|

55 |

III |

Urology |

Propofol, sevoflurane, N2O, fentanyl |

He heard the doctor ask for a stent which was identified by a number. He heard conversations off in the distance. No pain, no sensation of paralysis. |

|

46 |

II |

Cervical stenosis |

Propofol, desflurane, N2O, fentanyl, morphine |

Sensation of two flat surfaces moving on each other leaving sharp, intense pain. Felt sensation in the neck, sensation of choking and felt bone being cut away from the neck. |

|

70 |

II |

Abdominal |

Isoflurane, N2O, fentanyl, nmb |

The patient said she felt the incision and characterized the awareness as having associations with pain, paralysis, or stress. Patient said she had had recurrent memories about the operation. Patient states she has awareness of “the cut” but was unable to tell anyone. Afraid the pain was going to get worse, but it didn’t and then she went to sleep. |

|

59 |

III |

Vascular |

Isoflurane, fentanyl, morphine, ketorolac, nmb |

Claimed to remember a tube being put down his nose and vomiting. Characterized the experience as associated with pain, paralysis, or stress. |

|

44 |

II |

Left video thoracoscopy, excision of paraspinal tumor |

Induction: midazolam, propofol, fentanyl, isoflurane, fentanyl, nmb |

Patient remembers waking up on her side, unable to move, left arm suspended, with a breathing tube in her mouth. Remembers feeling pain on incision and the surgeon’s voice saying “she’s moving.” |

|

69 |

III |

Removal of hepatic artery infusion pump |

Induction: midazolam, propofol, fentanyl Maintenance: N2O, nmb |

Patient told the anesthesiologist he felt pressure at the surgical site during the operation but had no pain. He also heard voices and the instruments clanging. |

|

39 |

III |

Intracranial procedure |

Isoflurane, fentanyl, remifentanil, nmb |

He reported hearing the sound of something being “screwed into my head.” He recognized and remembered the sound when he heard the ICP monitor being removed after the operation. |

|

46 |

II |

Orthopedic |

Isoflurane, N2O, fentanyl, nmb |

Reports remembering feeling pain in hip and having a dream that “was interrupted by the pain.” |

|

71 |

III |

Gynecologic |

Sevoflurane, nmb |

Reports remembering “being intubated.” Remembers the “tube in my mouth.” |

|

61 |

III |

Thoracic |

Not recorded |

Reports awareness of intubation, “tube going down throat,” as last memory before falling asleep. |

Discussion

Our estimate of the incidence of awareness is relatively conservative. If the cases of possible awareness are also considered, then the overall incidence of awareness increases to 0.36%. It is interesting to note that the incidence data from Sweden included several cases that were described as “possible” cases 3 on the basis of inability to confirm the reports. If we compare the incidence of awareness between this study and the data from Sweden including “possible” cases of awareness, our incidence of awareness is approximately twice that reported previously. It is also possible that knowing that they were participating in a study of awareness may have increased the incidence of patients’ self-reports. However, this would be true of all awareness incidence studies.

The detection of awareness depends on the interview technique, timing of the interview, and structure of the interview.

A single short postoperative visit by an anesthesiologist without use of a structured interview is unlikely to elicit many cases of awareness. We used the same structured interview that has been used in prior investigations 6,13,14. We interviewed patients in the PACU and again after seven days because it has previously been demonstrated that approximately 35% of cases are detected only at a delayed postoperative interview 3.

Approximately one half of the cases in our study were detected only at the second interview. The loss of follow-up at the postoperative interview would therefore bias our results in the direction of underestimating the incidence of awareness during anesthesia.

The descriptions of the awareness cases identified in this study closely resemble those reported previously 3–6. As might be expected, a significant proportion of the awareness episodes occurred either during endotracheal intubation or at surgical incision, i.e., times when the level of patients’ stimulation is highest. Patients reported auditory recollections, sensations of not being able to breathe, paralysis, panic, and pain (Tables 4 and 5), consistent with previous reports 3– 6. Our study did not assess the long-term psychological sequelae of intraoperative awareness.

Awareness is caused by the administration of general anesthesia that is inadequate to maintain unconsciousness and to prevent recall during surgical stimulation. Common causes include large anesthetic requirements, equipment misuse or failure, and smaller doses of anesthetic drugs 1. Our finding of an increased risk of awareness with sicker patients (ASA physical status III–V) undergoing major surgery (Table 7) may reflect the use of smaller anesthetic doses and light anesthetic techniques in sicker patients. However, specific details of anesthetic doses and intraoperative hemodynamics in patients with awareness compared with those without awareness were not obtained in this incidence study. Although female sex and younger age have been suggested as risk factors for intraoperative awareness on the basis of analysis of closed malpractice claims 7, our study found no association between sex and age and awareness during anesthesia.

Dreaming during anesthesia was described by 6% of patients in our study, and this is consistent with the common occurrence of perioperative dreaming reported in several small European studies 13,15,16.

Dreaming was more frequently reported in the recovery room than later after surgery; this is also consistent with earlier studies 15. Dreaming was associated with younger, healthier patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. The widely varying incidence in dreaming by study site (1.1%–10.7%) may reflect differences in patients or anesthetic drugs, or, alternatively, it may reflect bias in patient selection or responses between the geographically dispersed centers 16. The significance of dreaming and its relationship to awareness during anesthesia is unclear. In many cases, awareness during anesthesia is a potentially avoidable adverse anesthetic outcome. In light of follow-up studies suggesting that such “victims of awareness” 8 may exhibit significant psychological aftereffects, such as PTSD, attempts to further reduce its incidence are warranted.

Awareness occurred despite the usual clinical monitoring of anesthetic depth (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and end-tidal anesthetic monitoring) in this study and others 3, 5, 7, a monitor of cerebral function and depth of anesthesia may be of theoretical benefit.

One such monitor, the BIS monitor, is a complex processed EEG derivative that assigns a numerical value to the probability of consciousness. Recovery of consciousness during general anesthesia without any recall (in the absence of surgical stimulus) has generally been associated with BIS values _60 17,18.

Cases of awareness during surgical stimulation with high BIS values (_60) have also been reported 19,20.

Although there is at least one case report of awareness with a BIS of apparently _50 21, BIS was subsequently found to be _60 at the probable time of awareness 22. In the present study, a number of the cases of awareness in which BIS was used also had high BIS values (see, for example, Fig. 2). We were unable to positively identify any cases of awareness with BIS values _60, but no firm conclusions can be drawn from this observation. This study was not designed to test the efficacy of BIS monitoring because the population that received additional monitoring was not randomly selected or matched to those who did not, and no specific guidelines for BIS were used. Other emerging data suggest that BIS monitoring is effective in reducing the incidence of awareness.

Ekman et al. 23 investigated the incidence of awareness when the anesthetic was guided with BIS and found a 77% reduction in the incidence of awareness 23 compared with historical data 3. Myles et al. 24 also found that, in a double-blind study of patients at high risk for awareness, BIS-guided anesthesia resulted in an 82% reduction in the incidence of awareness. In summary, the incidence of awareness during general anesthesia in the US was 0.13%. It occurred at a rate of 1–2 per 1000 patients interviewed at each site.

References

1. Ghoneim MM. Awareness during anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2001;92:597–602.

2. Myles PS, Williams DL, Hendrata M, et al. Patient satisfaction after anaesthesia and surgery: results of a prospective survey of 10,811 patients. Br J Anaesth 2000;84:6–10.

3. Sandin RH, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Lennmarken C. Awareness during anaesthesia: a prospective case study.Lancet 2000; 355:707–11.

4. Osterman JE, Hopper J, Heran WJ, et al. Awareness under anesthesia and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001;23:198–204.

5. Moerman N, Bonke B, Oosting J. Awareness and recall during general anesthesia: facts and feelings. Anesthesiology 1993;79: 454–64.

6. Ranta SO, Laurila R, Saario J, et al. Awareness with recall during general anesthesia: incidence and risk factors. Anesth Analg 1998;86:1084–9.

7. Domino KB, Posner KL, Caplan RA, Cheney FW. Awareness during anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1999;90:1053 61.

8. Lennmarken C, Bildfors K, Enlund G, et al. Victims of awareness. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002;46:229–31.

9. Rampil IJ. A primer for EEG signal processing in anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1998;89:980–1002.

10. Johansen JW, Sebel PS. Development and clinical application of electroencephalographic bispectrum monitoring. Anesthesiology 2000;93:1336–44.

11. O’Connor MF, Daves SM, Tung A, et al. BIS monitoring to prevent awareness during general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2001;94:520–2.

12. Kalkman CJ, Drummond JC. Monitors of depth of anesthesia, quo vadis? Anesthesiology 2002;96:784–7.

13. Brice DD, Hetherington RR, Utting JE. A simple study of awareness and dreaming during anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1970;42: 535–41.

14. Liu WHD, Thorp TA, Graham SG, Aitkenhead AR. Incidence of awareness with recall during general anaesthesia. Anaesth 1991; 46:435–7.

15. Ghoneim MM, Block RI, Dhanaraj VJ, et al. The auditory evoked responses and learning and awareness during general anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2000;44:133–43.

16. Hellwagner K, Holzer A, Gustorff B, et al. Recollection of dreams after short general anaesthesia: influence on patient anxiety and satisfaction. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2003;20:282–8.

17. Flaishon R, Windsor A, Sigl J, Sebel PS. Recovery of consciousness after thiopental or propofol: bispectral index and the isolated forearm technique. Anesthesiology 1997;86:613–9.

18. Glass PSA, Bloom M, Kearse L, et al. Bispectral analysis measures sedation and memory effects of propofol, midazolam, isoflurane, and alfentanil in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology 1997;86:836–47.

19. Luginbuhl M, Schnider TW. Detection of awareness with the bispectral index: two case reports. Anesthesiology 2002;96: 241–3.

20. Bevacqua BK, Kazdan D. Is more information better? Intraoperative recall with a Bispectral Index® monitor in place. Anesthesiology 2003;99:507–8.

21. Mychaskiw GI, Horowitz M, Sachdev V, Heath BJ. Explicit intraoperative recall at a bispectral index of 47. Anesth Analg 2001;92:808–9.

22. Mychaskiw GI, Horowitz M. False negative BIS? Maybe, maybe not! Anesth Analg 2001;93:798–9.

23. Ekman A, Lindholm M-L, Lennmarken C, Sandin R. Reduction in the incidence of awareness using BIS monitoring. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004;48:20–6.

24. Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, et al. Bispectral index monitoring to prevent awareness during anaesthesia: the BAware randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:1757–63. Statistical processing support was provided by Aspect Medical Systems, Inc. We thank Jeff Sigl, PhD, and Paul Manberg, PhD, from Aspect Medical Systems for providing statistical analysis and helpful suggestions during the preparation of this manuscript. We also appreciate the assistance of Scott Acker, RN, Antonio Adam, MD, Kerith Brandt, Catherine Dobres, CRNA, Samantha Goldstein, BA, Meghan Holmes, MA, Kui-Ran Jiao, MD, David Kramer, Yumi Lee, MD, Jason Leggio, CRNA, Tanya Lipto, RN, Lee McClurkin, RN, Rachel Pessah, BS, Jacqueline Sumanis, CRNA, Meghan Swardstrom, and Thu Tran, BS.